Do you know that even after independence, the Government of India did not give passports to Dalits - know what was the reason behind this-In the year 1967, the Supreme Court of India ruled that it is a fundamental right of every citizen to have a passport and go abroad. In India in the sixties, this decision was historic because at that time the passport was considered a document of a specific people.

|

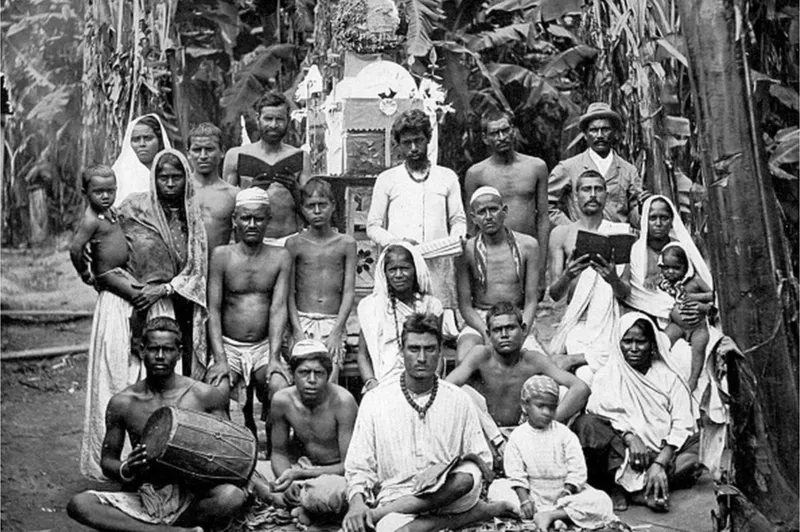

| IMAGE CREDIT-BBC HINDI |

Do you know that even after independence, the Government of India did not give passports to Dalits - know what was the reason behind this

At that time, passports in India were issued only to those who were considered capable of maintaining and representing India abroad.

Historian Radhika Singha, associated with Jawaharlal Nehru University, points out that for a long time after independence, the passport was considered a symbol of a citizen's status, issued only to eminent, wealthy, and educated Indian citizens.

This was the reason why passports were not given to workers living in Malaya, Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), Burma (present-day Myanmar), and the so-called indentured working class.

The number of people coming from these classes was more than a million who went to various countries under the control of the British Empire to work during colonial rule.

According to historian Kalthmik Natarajan, associated with the University of Exeter, "The holding of an Indian passport, as recognized by the Government, was thus considered a desired representative of India. This was considered 'undesirable'. And this practice continued after 1947 as a policy on Indian passports. dominated."

Changes in policies did not happen even after independence

Dr. Natarajan has scoured the archives to know in detail about the Indian policy of discrimination in passport distribution.

She informs that "the situation did not change even after independence from British rule. The new government also considered a certain section of its 'undesirable citizens' as high and low as the colonial state (British rule)." Keep doing it."

Dr. Natarajan says this distinction was made on the belief that foreign travel is associated with self-respect and dignity for India, so foreign travel could only be done by those who had 'India's honorable status.

In such a situation, the Government of India had ordered its officers to identify such citizens who would not embarrass India abroad.

In this, the state governments got the benefit of the policy of issuing passports till the year 1954. India tried to create a "desired" Indian diaspora community by denying passports to most people.

Conspiracy with British officials

Other researchers including Dr Natarajan have also found that after 1947 this policy was implemented in connivance with British officials to prevent people from lower castes and classes from going to Britain.

(According to the British Nationality Act 1948, Indian immigrants (Indians settled abroad) were allowed to come to Britain after independence. According to this law, all Indians living in India and outside India were considered British citizens).

Natarajan says that the officials of both countries created a category of Indian people that both sides did not consider fit to go to Britain. Both the countries were to benefit from this. For India, this meant stopping the descendants of the 'undesirable' poor, low caste, and indentured laborers from moving forward, who could possibly 'shame India in the West'.

For Britain, she says, this meant handling the influx of colored (who were not white) and Indian migrants, especially the nomadic class.

A covert report was presented in 1958 because of the problems caused by the large influx of immigrants (especially blacks) to the UK.

The report differentiated between West Indian immigrants "who are mostly good and mix easily with British society" and Indian and Pakistani immigrants "who are unable to speak English and are unskilled in all respects". was.

Natarajan says that the British realized that the immigrants from the subcontinent, most of whom were unskilled and unable to speak English, had a poor background.

A British official posted in the Office of Commonwealth Relations in the 1950s wrote in a letter that the Indian official expressed "apparently pleased" that the Home Department had "managed to repatriate some potential immigrants."

Dalits were not given passports

Researchers have found that under this policy, passports were not given to the most disadvantaged sections of the Scheduled Castes or Dalits in India. Dalits account for 230 million of India's current population of 1.4 billion. Along with this, passports were also not given to political unwanted members such as members of the Communist Party of India.

Members of former separatist regional parties like the DMK were denied passports in the 1960s, flouting guidelines for granting passports to MPs, MLAs, and councilors without financial guarantees and security checks.

There were other ways of not giving a passport. Applicants had to take literacy and English language tests, a prerequisite for having sufficient funding and complying with public health regulations.

British Indian writer Dilip Hero recalls that in 1957 he had to wait six months to get a passport, even though his academic education and financial condition were very good.

Such oppressive control brought results that no one could have imagined. Many Indian citizens got fake passports.

Following such scandals, illiterate and semi-literate Indians who did not know English were disqualified for passports sometime between 1959 and 1960.

As such, for nearly two decades, India's passport system was not equally available to all who wanted to travel to the West.

A glimpse of this policy was also seen in 2018 when PM Narendra Modi's government announced plans to introduce the Orange Passport with the aim of helping and assisting Indians with unskilled and limited education on a priority basis. Whereas usually, the color of an Indian passport is blue.

There was strong opposition to this plan, after which the government had to withdraw this proposal.

Natarajan says that such a policy only suggests that India has long viewed the international world as a place that was suitable for upper caste and class people.